Moving to Idaho

I am moving my permaculture operations to Idaho Falls, Idaho. I am defining permaculture rather loosely here. To have a more sustainable world, we must re-envision the world that we have. In our striving to have a new vision of the world, creative projects are useful. A created object, like an essay or a painting, is as essential to a sustainable culture as are methods of growing tomatoes. So with that idea in mind, my blog is, at present, my contribution to Permaculture.

Coming back to my home state has made me curious about the relationship between place and its influence on my biography. Culture is a narrative, a story. Each one of us has a fractal part of a larger cultural story. That larger story is the framework for our own values and beliefs. The history of Idaho was the larger frame of my family’s history and my own story.

I am staying with my sister and brother-in-law before returning to Europe. Their household is eccentric and extremely comfortable.

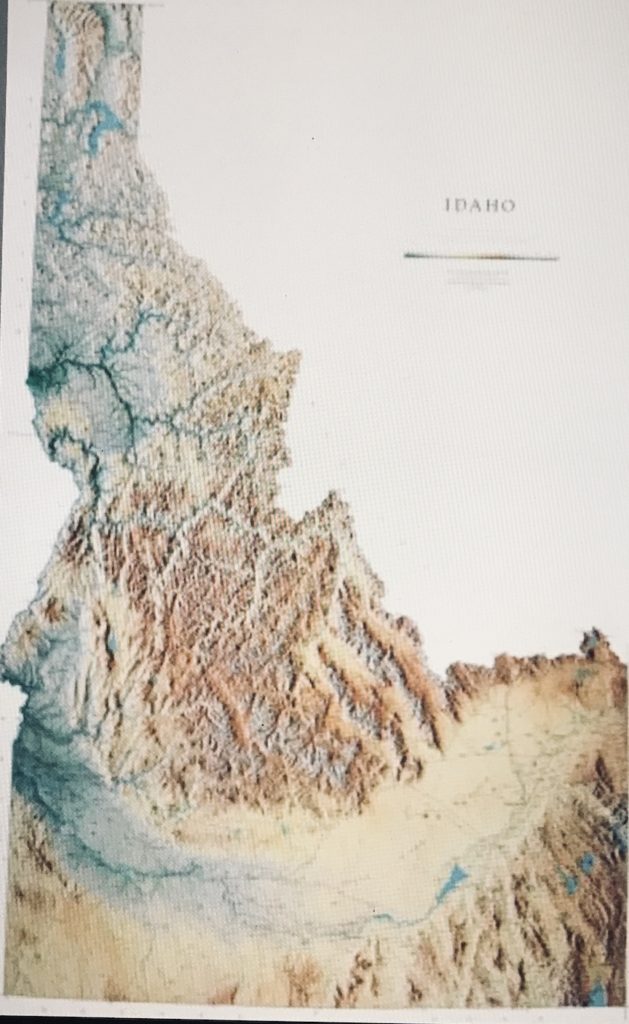

Idaho is the same size as Austria. It once had the largest white pine forests in the world. It still has the largest primitive area within the continental US. The entire central part of the State is impenetrable, except by air or pack train. Since the mountains are relatively new and made of volcanic rock, the state is rich in gems and valuable minerals. The early settlers, in my grandfather’s day, came for the timber, the mines, and the cattle ranges. And after the Snake River was dammed, they grew famous potatoes.

When I was in high school, about 500 thousand people made up the entire population of the state. This has changed since large corporations started moving in fifty years ago. But there is still only one state highway in Idaho that runs north to south, and except for Boise, there are no large cities.

History of Idaho

Idaho history was a mandatory course I had to take in College at the University of Idaho. The text for the course was just this side of being as tedious as reading a telephone book. In the course, I learned that my hometown, Moscow, Idaho, was the split pea capital of the world, and Bonneville county had the same status for potatoes.

The course never mentioned that during my grandfather’s day in the early century, all of the working men, miners and timberjacks, were locked in stockades to prevent civil war, The Wobblies were running amuck and the one of them assassinated the governor. (not mentioned). The text may have spoken of the Nez Perce, Bannock, and Shoshone people but not the fate of those bravest of warriors that refused to stay on reservations. There was no mention of range wars or the inside deals achieved by the State fathers to carve up the timber and mineral wealth of the state.

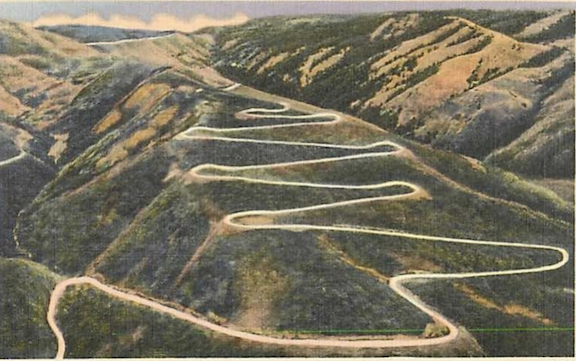

I learned the history of the Indian wars from getting carsick on the mountain passes between Moscow and Boise. I’d stumble green from motion sickness out of our car on White Bird Pass to be confronted by a sign that would read: Chief Joseph, Chief of the Nez Perce Indians, passed here in April of 1876, with 50 braves and 300 women and children, evading the US cavalry.

And further down the mountain: “Captain David Perry, leading 130 soldiers fought here against 70 Nez Perce in the battle of White Bird Canyon in July of 1877.

Nine months after this battle, the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph, surrendered, freezing and starving before they reached the Canadian border. They had managed to evade the US Cavalry for two years. They were put on reservations but Joseph was never allowed to back to his people. I knew Joseph’s great grandson. He was a poet and a serious alcoholic, even in high school. He died frozen to death on New Year’s Eve in 1977. It was more than their land that the Nez Perce lost. It was their story.

The Nez Pierce

Although the Nez Perce were heavily outnumbered in the Battle of Whitebird Canyon, they had an advantage over the US Calvary. The Indians bred Appaloosa horses for war. They were smart, tough horses that would not flinch in battle with a rider fighting on their backs. The horses got their name from where the Nez Perce bred them, the Palouse, a French name, (Like Nez Perce) and the part of Idaho where I was born.

People are made of stories, narratives that define belief and a sense of what is real. The substance of a person is a story as much as bone and blood; for the story is what animates and compels the course of life. Embedded in a story are the beliefs, values, and purposes of a specific culture.

My great-great-grandfather settled in the area impinging on the land of the Nez Perce tribe in the 1850’s. I was unaware of this relationship to Chief Joseph when I was throwing up on his monuments. But our stories collided in different ways.

I realize that Chief Joseph and my ancestors represented two different stories that were completely incompatible. The narrative of Manifest Destiny, emerging from the European Enlightenment, smashed the world of the indigenous people we encountered. It was more than their land that was taken, it was their story. And without their story, they fell into despair. I am thinking of this now, because the limitations of the mythology within my own culture is now fraying and coming apart. We need a new version of our own story to survive.

My Great-Great-Grandfather, Johnathan Tipton Wiseman, homesteaded land impinging on Nez Perce land in 1852

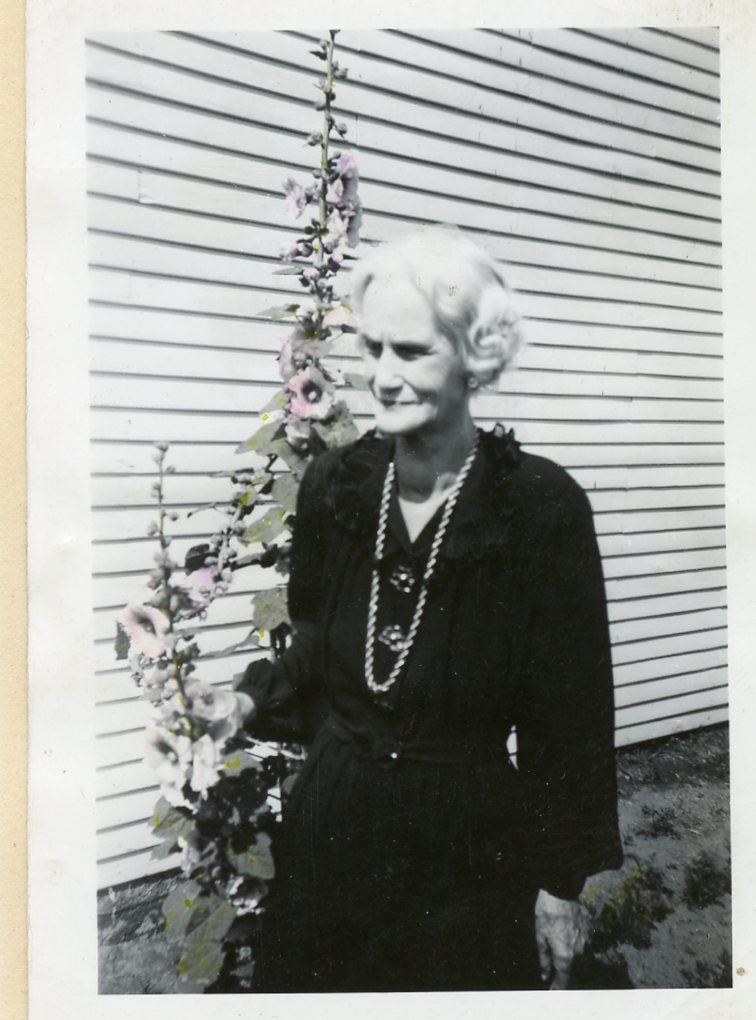

His daughter, Francis Wiseman, is my great-grandmother

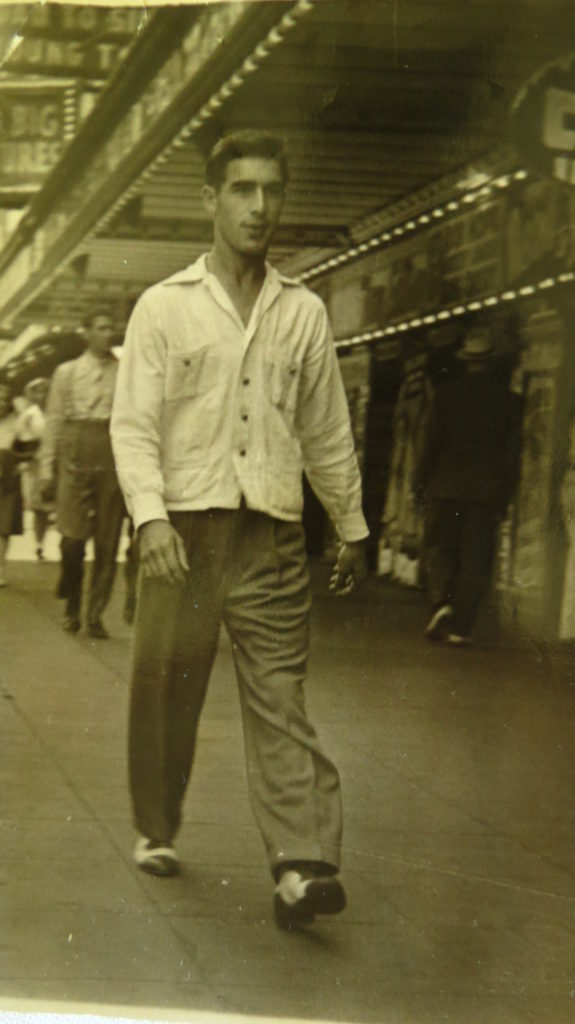

My grandmother, Bonnie Cope,daughter of Francis Wiseman. (Far right) my father, Cope Gale, great grandson of Johnathan Tipton Wiseman

There are many stories within stories in my life, but the over-arching narrative in my family was one of westward movement. I have traced four families in my ancestry back to Virginia and Massachusetts in the early 1600’s. They moved west for generations, traveling through Arkansas, Tennessee, the Dakotas, traveling by wagon train or following the railroad as it was built.

I had a history professor in college heavily influenced by Frederick Jackson Turner. Turner’ linked what was called, “American Exceptionalism” to the frontier experience. This theory is in disrepute today. But aside from the self-aggrandizing elements within his theories, I believe Turner was right. The frontier experience changed the American character.

In Idaho, there is still a local sense of independence, self-sufficiency and a kind of honor code that was characteristic of the frontier; at least it can be found in families who have been here generations. My favorite historian, William Irwin Thompson, claims that even with the wholesale slaughter of the indignous people, Native American values and philosophy still seeped into our common wisdom and had a profound affect on American culture.

For my own part, I experienced the shadow side of local culture. The isolation of the frontier, of being cut off from the vibrant creative culture of large cities, meant that the ecosystem of ideas, of the arts, and other cultural activities, remained remote in the time I was growing up and I have not lived in Idaho for forty years. Idaho is a place where people are still more in tune with the natural landscape. This, in the end, may be more of an advantage in our current dark age than I thought.

My brother Cope sent me this additional information on Idaho history and the assassination of the governor, which I am including here.

On December 30th, 1905 when Harry Orchard installed what we now call an Improvised Explosive Device on the gate of Ex-Governor Steunenberg’s residence in Caldwell, it was the culmination of several years of skulduggery and violence. Among other crimes, in June 1904 Orchard had placed two boxes of dynamite under the platform of the Independence railroad station in Colorado where strikebreakers were gathering to go to work in the mines. When he detonated it, it killed 13 workers and injured many more. Six endured amputations. Back in Caldwell, at 6:45pm, 44 year old Frank Steunenberg pushed open his gate and detonated the bomb. After finding bomb making material in Orchard’s hotel room. he was arrested. Idaho governor Gooding was persuaded to hire the Pinkerton Detective Agency to investigate Steunenberg’s murder. Pinkerton agent, James McParland had Orchard moved from the Canyon County jail in Caldwell to Death Row in the Idaho penitentiary on Warm Springs Ave. in Boise..McParland, famous for sending 10 Molly Maguire members to the gallows, had Orchard placed in a cell beside two inmates awaiting execution. After a couple weeks on sparse rations he met with Orchard in a private room for a luxurious meal and cigars .McParland told stories of criminals who became state witnesses who received their freedom plus $1000 for resettlement. Orchard confessed and told how he was put up to the evil deed, and many others, by the leadership of the Western Federation of Miners. Steununberg had been elected with the help of labor and when he called in federal troops to quell strikers in the Coeur d’Alene mining district in 1899, they felt betrayed.

Bill Haywood, Charles Moyer and George Pettibone were arrested in the middle of the night in Colorado and transported to the Idaho State Pen on a special train. (no extradition papers needed) In the trial the Union Members were defended by Clarence Darrow. The prosecution was headed by James Hawley. (soon to become Governor in 1911).

Haywood was tried first, In what was termed the trial of the century, Orchard, under intense cross examination by Darrow, never strayed from his story and never contradicted himself. However, his meetings with the defendants could not be collaborated by anyone else. When judge Fremont Woods instructed the jury, he told them that if there was no collaboration, they would have to find the defendant not guilty. ,And this they did.

In the 7th grade while studying Idaho history, our class sat at their desks and listened to a weekly history lesson, broadcast on the radio and sponsored by J.R. Simplot. Somehow they missed this chapter.

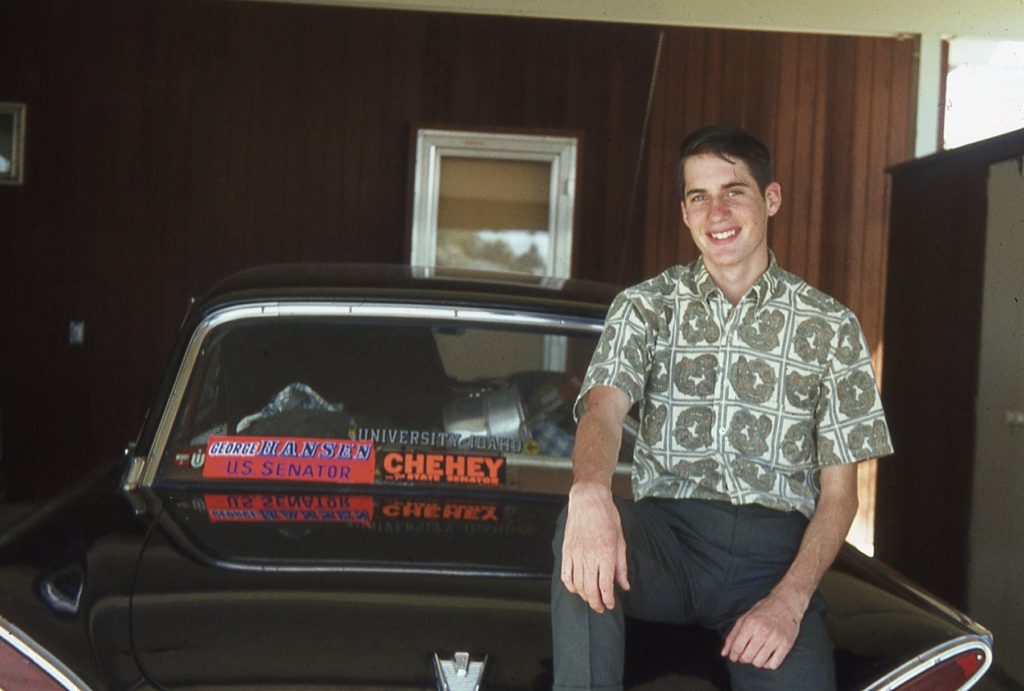

Cope Gale Jr. 1967(?)