MY RELATIONSHIP TO EDVARD MUNCH

My college painting instructor, Mary Kirkwood, was a remarkable woman. I am remembering her lately because I am making a video for my online high school art course on painting a still life, and began ruminating on my own style of painting.

Generally, the only time I paint something is when I need to do a demonstration. I realized my demonstration did not work with small details and I wanted to explain to potential students in my video, that still life painting has changed since the days of the Dutch Masters when painters were concerned about small details.

I realized that how I painted and thought about painting technique was based on my own training from Mary.

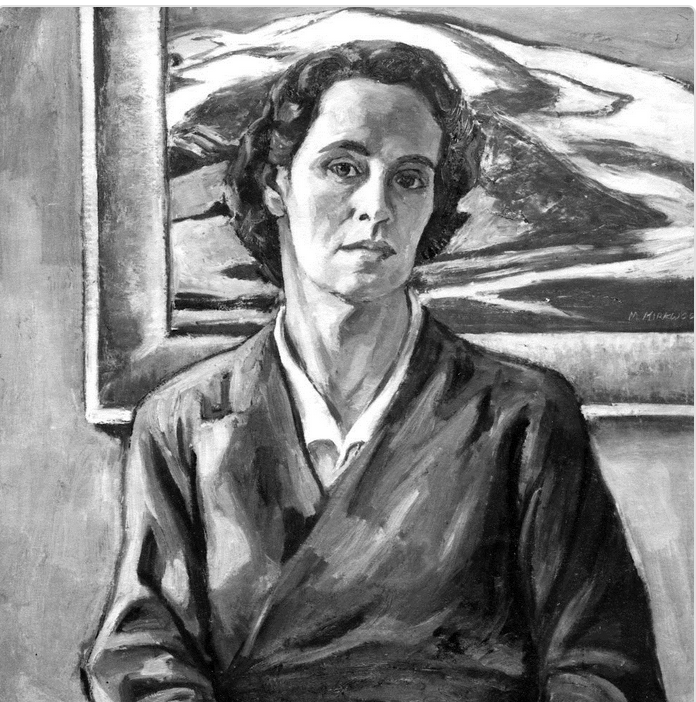

Mary’s self portrait here, shows a style strongly influenced by Expressionist painters in the early century, particularly Edward Munch, because Mary did post graduate work at the Royal Art School in Stockholm in the 20’s, where Munch had a strong influence.

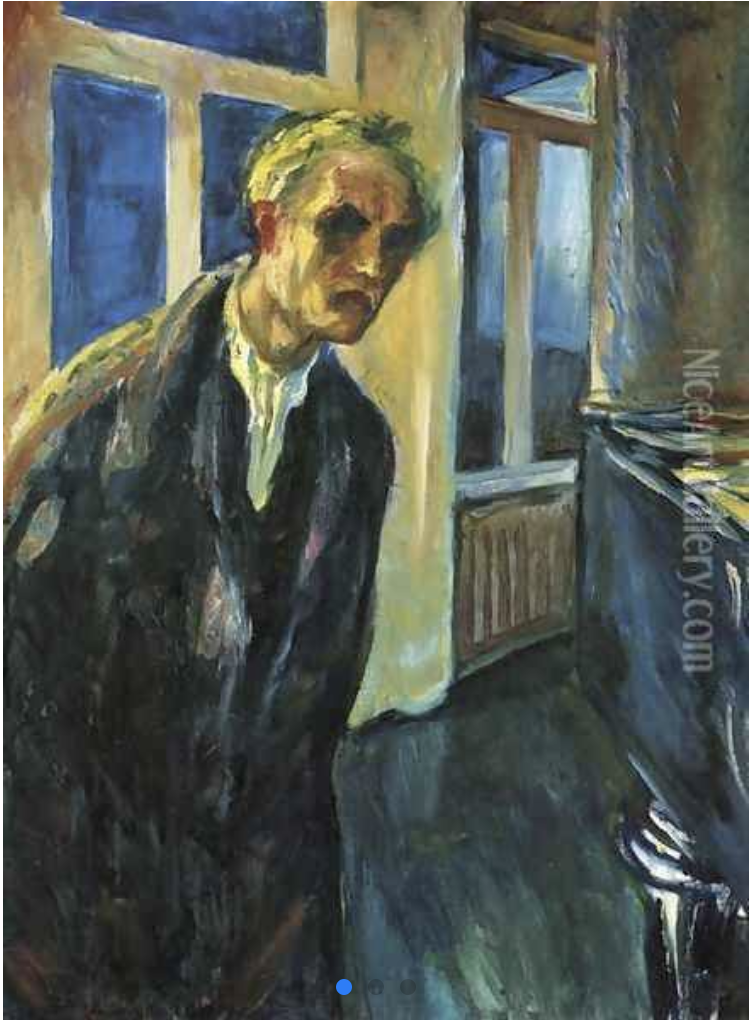

This self portrait by Munch was painted in 1926, two years before Mary’s arrival in Stockholm. It was not until I started the video with my painting demonstration, that I thought of Munch’s influence on my teacher. I had known of it years ago but without any sort of perspective.

Of course, saying painters were influenced by Munch is like saying biologists were influenced by Darwin. But Munch had a particular kind of palette and quiet, emotional intensity that was somewhat unique to his work at the time.

Whatever influence the German Expressionists had on me was diluted to using dark colors and broad brushstrokes. I cannot claim Munch as a muse, but the German Expressionists did play a part in how I paint.

Mary painted me in 1980. The decade before that had been a difficult one for her professionally. The art department at the University of Idaho, where she was department head, had expanded their faculty from three to five. The two young men hired were disdainful of her work and colluded with students to dismiss her work and criticize her personally.

It is hard to remember the cultural mood of the day, now some fifty years ago, but these men, who were arrogant and stylishly profane, suggested she would be better off painting china. For them her painting style was outdated and irrelevant. They added that she needed to get laid. (Mary was a spinster).

The people criticizing her extended to the wife of the head of the department of Art and Architecture, who publicly said that Mary’s work was not keeping up with the times; as if she should have dropped everything to paint soup cans or Rothko-esque color fields.

This was an era when no one of any note was doing figurative work. Philip Pearlstein was credited with reviving figurative painting in the 70’s. Mary’s sin was that she had never stopped. In any case, Pearlstien’s work was cold, impersonal, and he painted nudes as if they were furniture.

Mary’s statement to her critics is written below:

“Painting the human figure is to me more than satisfying. After some confusion in earlier years about keeping up with the changing movements, I came to realize that painting was more than a body of knowledge or even a way of thinking; it was a way of feeling, and feeling could not be altered casually by events outside of one’s own nature or the vital experience that had roots in one’s youth.”

Mary did experiment with other painting styles, from the Socialist Realists, pure abstract painting, and landscape painting.

But she always came back to figurative painting because she found her most authentic expression there.

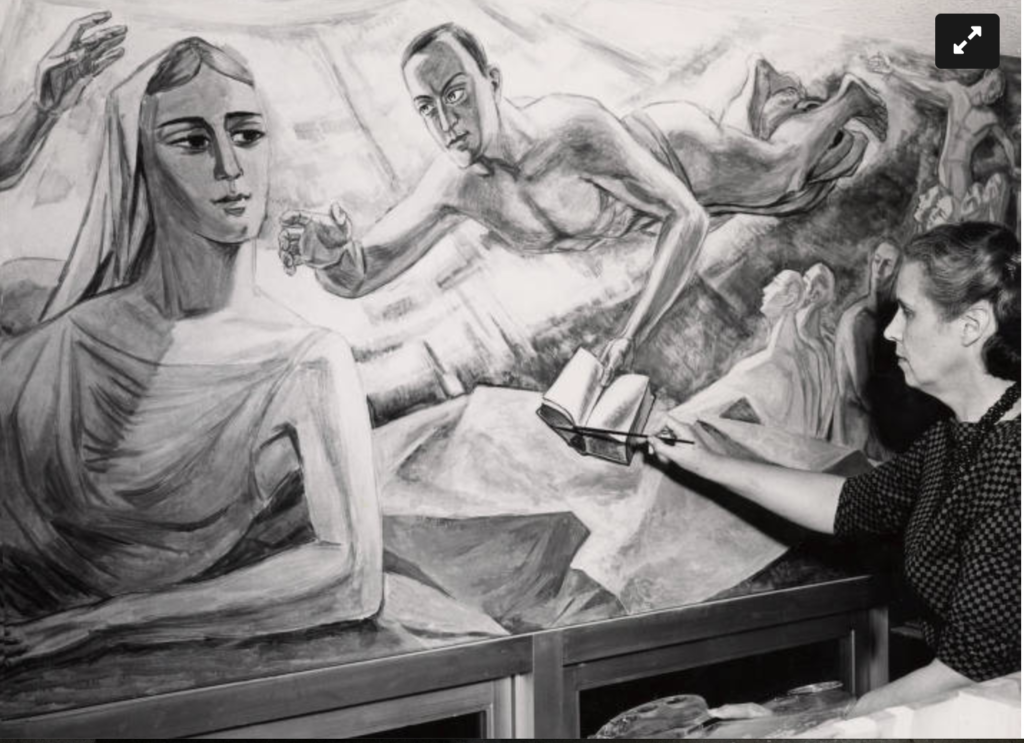

This portrait by Mary of Craig Shipley has the kind of emotional intensity familiar in Munch’s work. It was painted shortly before Craig killed himself.

Craig had taken a lot of LSD and couldn’t stop the voices in his head, but he was a good artist himself. He was with me in Mary’s Composition class. Mary would list all of the rules of composition and Craig would break every one of them. His work was always the best thing in the class.

Painting styles aside, this portrait could be another version of, “The Scream.” But beyond that, it is a marvelous painting and I see it differently than I did in my clueless youth.

Mary fought to be who she was in an era when professional women, particularly unmarried professional women, were dismissed as neurotic and less-than; and when her approach to art was considered out of fashion.

Mary was not aggressive or bold in any way, but she had a deeper kind of courage, one that insisted on being true to herself in the face of ridicule and ignorance.

I seem to be re-writing the events of my life backwards. What appeared to be so important at the time is forgotten, and those things I barely noticed take on a profound significance. All the hysterical enthusiasm for this or that Abstract Expressionist or Pop Art icon, would fade into the final pretensions of Post Modern Art. Such is the nature of culture.

I did not capitalize on Munch’s genius through Mary by becoming a painter. But I learned a lot about being a teacher from her. That said, the knowledge took a few decades to cement into practice.

When I think of it now, what she really taught me was how to value my own way of being, not fear my own mediocrity, while being the most authentic version of myself I can muster.

,