The River

I arrived in Idaho Falls where I had lived as a twenty-something, from Slavonice amid great difficulty (within the travel industry) and quarantined for five days at a hotel on the Snake River.

Heraclitus said you never step in the same river twice. But Mark Twain said history never repeats itself, but it rhymes. If I can be so free as to mix metaphors between the river of Heraclitus and the river of history, then I would be on the River Livy in Finnigan’s Wake as well as the Snake River in Idaho.

“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

James Joyce

Moving between physical rivers, historical rivers, and literary and mythical rivers, is all in a day’s work for me because skipping between the modalities of perception provides a form of orientation. Just as when a moment of synchronicity reveals patterns, following the mythological meaning of events in my life, following mythological patterns in my own life is how I find an “X” that marks the spot where I am standing.

So I have come by a commodious vicus of of recirculation, back to the west bank of the Snake river and to remembered scenes from my feckless youth, because life moves in a circle and rivers represent a story. In this case, my story.

The river is mostly frozen, but still moving, and will begin to move faster as the light comes back into the world. Spring is a month away. And just as the death and re-birth of the solstice promised, my life is beginning again, but in a new form.

My hotel on the river was once called the Westbank. The attached coffee shop was like“Cid’s” in Happy Days, back when I was young. Everyone went there after the bars closed on Saturday night. This is no longer the case, but the hotel and restaurant still sit on the most breathtaking view of the river.

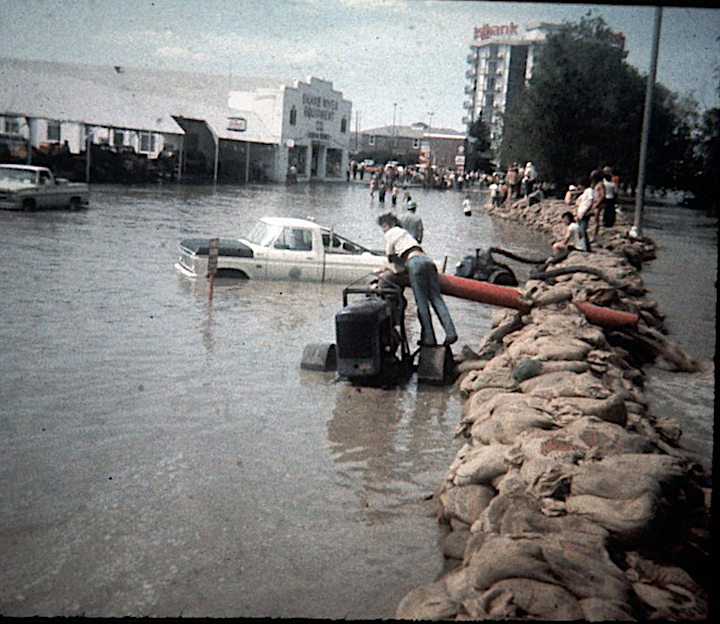

The headwaters of the Snake begin in Yellowstone Park and move west, through Idaho Falls. A dam upstream broke in 1976, sending a deluge downriver and threatening the Westbank. No one moved a finger to save the businesses up stream from the hotel, but when the hotel and coffee shop were threatened, the entire population of Idaho Falls between the ages of 20 and thirty-five, turned out to sandbag the banks of the river and save their favorite bar and coffee shop.

The Teton dam failed because of self-serving politicians and incompetent engineers who built the dam in spite of active lawsuits to stop them. Water and the proper use of the Snake River, as defined by the federal government, has been a battlefield since the beginning of the State’s history.

When the dam failed, eleven people died, along with thousands of cattle. Multiple small communities were wiped out. The dam was never re-built.

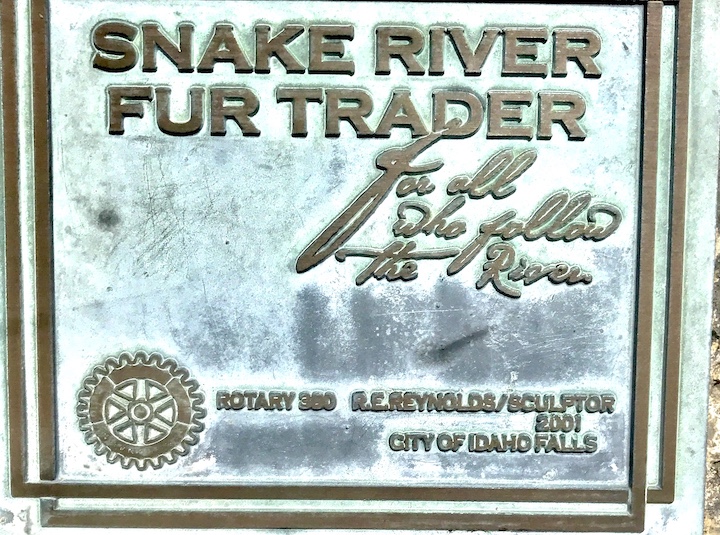

For all who follow the river...

I was born in the north of the state, but I was once married to someone from Idaho Falls. He and his brother are/were artists. My brother-in-law, Roy Reynolds, died in September, leaving behind a rich trove of paintings and sculpture, much of it representing life along the Snake River.

The sculpture above was made by Roy in 2001, of a figure that would have been known along the Snake a hundred and fifty years ago: a trapper and what was once called a Mountain Man, the first Americans of European descent into this part of the world. Roy designed the face of the Trapper after his own face. I think he strongly identified with the archetype portrayed in the statue.

Roy was one of the most gifted artists I have even met. He was a talented graphic designer and illustrator as well as a fine artist; and he is a friend I will miss

Oceans and lakes are feminine, passive, and the province of the Great Mother; otherwise, they are symbols of the collective unconscious. But rivers are male, they are creatures of action and address the narrative of time; the act of becoming.

From the perspecrice of my own life, my world is emerging out of the deluge of a biblical flood and back into time, into a moving river. Considering the confusion, world-wide, of the past two years, I am expanding my personal mythology to include the collective.

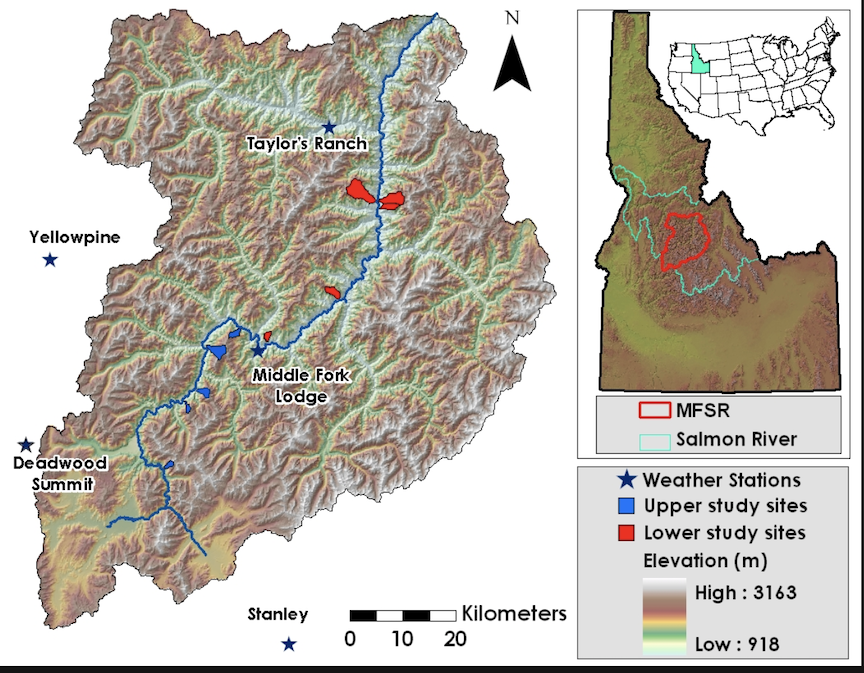

The Salmon and the Snake

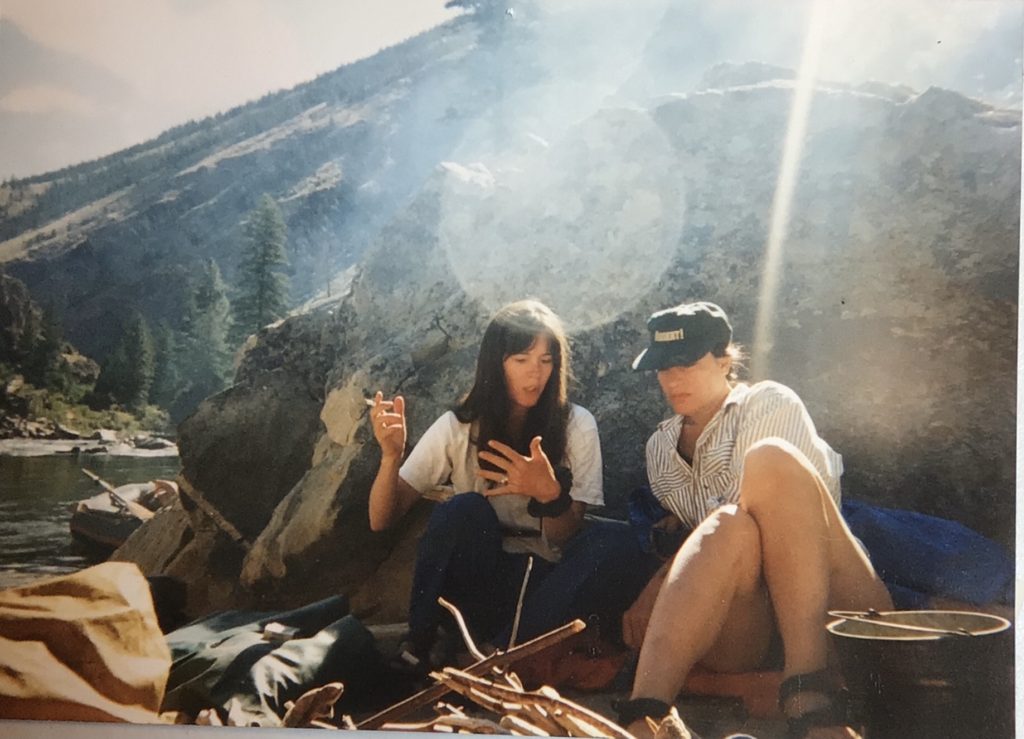

My brother-in-law, Steve is very familiar with Idaho rivers and all of their tributaries. The Snake is fed by rivers west of the Continental Divide and drains into the Columbia. Steve’s father and brothers have worked as fire-fighters and land management agents of both the State and the Federal government. When he was in law school, Steve led white water rafting trips down the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, a main tributary of the Snake, and he has worked in the Idaho primitive area, leading pack-trains into places where there were no roads since he was a teen-ager.

Steve is aware of all of the drainage systems west of the Rockies and probably east of them too; and he is aware of the politics surrounding water use in the Western States in general. But his heart is most attached to the Salmon River, and to the fate of the indigenous wild fish, notably Salmon, who migrate up the Columbia from the Pacific, eight hundred miles, to the center of Idaho.

Since a series of dams have been built on the lower Snake in the seventies, the population of Salmon able to make it to their historic spawning grounds has diminished to almost zero because four dams have created miles of slack water that used to be a flowing river.

Past studies have estimated that the Salmon River once supplied 40 percent or more of all the Chinook Salmon found in the Columbia Basin. With each dam built on the lower Snake, the number has been diminished until there were almost none.

There was an effort to replace the wild fish with farmed fish, efforts that failed to replace what was lost, as far as Steve is concerned.

I am mining Steve’s correspondence to a government agency that controls environmental issues for the Columbia River Basin. His advocacy for the wild rivers of Idaho argues a counter narrative to the progressives of the 1970’s who built dams on the lower Snake River.

Excerpts from Steve’s letter to a government agency that controls the waters of the Columbia Basin:

“I was born in 1955, and when I was a young boy, the upper tributaries of the Salmon River still ran pretty thick with wild fish naturally spawning in their native streams. My grandparents fished for those fish for a month or more each year, and had done so since the 1920s. They packed into what was then the Idaho Primitive Area to fish the Middle Fork of the Salmon, where they said the country still had dew on it from the morning of creation, and the fishing was beyond belief. They witnessed the reason Redfish Lake is called Redfish Lake, when it teemed with blood red sockeye. In the 40s and 50s, my Dad jumped on forest fires in the central Idaho wilderness and talked of all the salmon he saw spawning in nearly every stream.

But during that same time frame, things were changing. Suddenly, it seemed like fewer and fewer fish were around. One no longer routinely saw them rolling in the eddy lines along the upper Salmon. One had to struggle to find a spawning pair in Bear Valley Creek. Seasons were curtailed and closed. By the time I was working in the central Idaho wilderness during the mid 70s, you didn’t see them rolling much along the still pristine Middle Fork either. When I guided on the Middle Fork in the early 80s, we used to count ourselves lucky to see a very few jump at Dagger Falls in an entire season, even though we were there once a week. Likewise, it was no longer possible for generations younger than my own to see for themselves why Redfish Lake even bore that name.

So what happened? Between 1957 and 1975 the Corps of Engineers built six new dams on the Columbia/Snake system between then existing Bonneville Dam and Lewiston, Idaho — the Dalles in 1957, Ice Harbor in 1962, Lower Monumental in 1969, Little Goose in 1970, John Day in 1971 and Lower Granite in 1975. Suddenly Salmon River fish had to negotiate eight dams and reservoirs instead of only two (Bonneville and McNary). Six new dams in 18 years, the net effect of which, from the fishes’ standpoint, was to turn the largely free flowing lower Columbia and Snake Rivers into a single 325 mile long stagnant pond, and place six new concrete impediments in their path to boot.

Salmon River anadromous fish are a tough bunch. They’re strong and they’re resilient. They have to be, because they travel over 800 miles from the ocean to spawn in their natal streams, farther than any other anadromous fish in the Columbia Basin, and perhaps, in the world. Then the next generation of fish have to navigate that same remarkable distance back down to the ocean to start the cycle all over again, a cycle that was endlessly repeated over and over again by millions of fish for thousands of years, through volcanic eruptions, floods, earthquakes, landslides, fires, adverse ocean conditions and other assorted natural disasters. So Salmon River fish are tough and they can handle a lot of adversity, whatever mother nature threw at them. By all indications, they could even handle the 40 some odd miles of slack water behind Bonneville Dam and another 40 or so behind McNary. But to me it’s clear that they couldn’t handle the continuous 325 mile slack water pond and associated concrete impediments placed in their path between 1957 and 1975. At that point, eight dams and the continuous slack water they created became just too much, more than they could bear, even for a tough bunch of fish.

Since those dams were built, it seems to me that the dam builders and their allies have spent the last 30+ years focusing on and/or attempting to mitigate other collateral issues, apparently desperate to avoid directly confronting the obvious issue, which is the existence of those dams and the slack water they create. Oh, no fish? No problem they say, we’ll finance more and more hatcheries with all these hydropower dollars that are rolling in. To me, that’s somewhat akin to saying we can let the elk all die out because after all, we can just replace them with more cows. The fact is, hatchery fish are no substitute for wild fish, and that is particularly so when it comes to the Endangered Species Act. Yet in recent years, the powers that be continually tout the “record salmon runs,” as if all those hatchery fish were somehow the equivalent to true wild fish recovery. To me, that is nothing short of a shallow political ploy intended to disguise the fact that wild fish are and have been in serious trouble for a long time. Indeed, a truly cynical mind might wonder if the actual design might be to ignore the plight of wild fish long enough for them to go extinct.

From all that I have read, the four dams on the lower Snake were marginal projects from the beginning, built at the end of the dam building era by an agency looking for more projects to build, and sold to the public as a means to turn Lewiston into a great port city filled with bustling barge traffic, and to generate a little more hydropower, an already abundant resource in the pacific northwest at the time. They serve no significant flood control, irrigation or recreational need, and they never did. Today, 40 plus years after the last dam came online, Lewiston is far from the bustling port city that was touted at the time. In fact to my eye, it hasn’t changed much since I was attending college just north of there in the mid 70s. Barge traffic has been declining for years from an early peak, and now the Corps has to periodically dredge the channel for several miles downstream to clean out the accumulated sediment caused by Lower Granite, and thereby hopefully avoid flooding the town and assuring the largely unused port stays open. The hydropower the dams generate remains un-needed, and some say the continued operation of them is nothing more than a burden on the taxpayers. In the meantime, recent dam removal projects elsewhere in the pacific northwest have demonstrated how quickly natural anadromous fish runs can be restored when dams are removed.”

End of excerpts

_______________________________

One could argue that the cause of the salmon wild fish population is not so important to the general population and beyond a small group of fishermen. But the over-arching issue concerns the rubric we use when we alter the natural landscape so radically.

A wiser understanding of our relationship to the natural environment is emerging in our present existential crisis, long after the promise of the slogan: “Better Living Through Chemistry” defined the values of my own generation.

My question is, what is the cost of killing a river, changing it to a lake? As I said at the beginning of this blog, a river is a narrative, a story that is moving. The action of the river makes a story– and we alter the story when we alter the river.